Trade and Foreign Aid

EC 390 - Development Economics

2025

Trade

Why is Trade Is Important

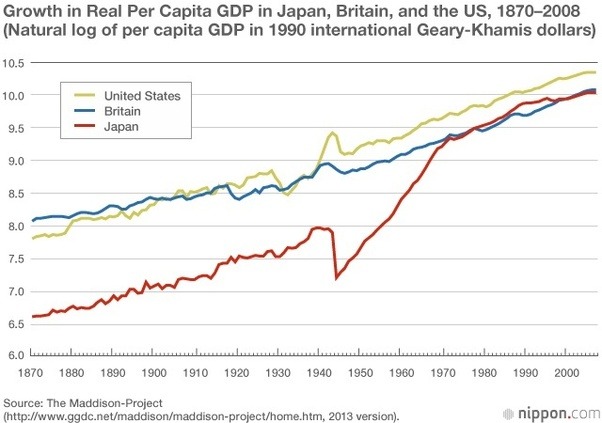

Case Study: Japan

Japan’s economic growth after WWII was large

- Trade played a large role

- First they exported textiles

- Then started exporting more advanced consumer goods: Electronics, vehicles, machines, etc.

- Exports increased from 19 Billion USD in 1970 to 270 Billion USD in 1989

Case Study: Japan

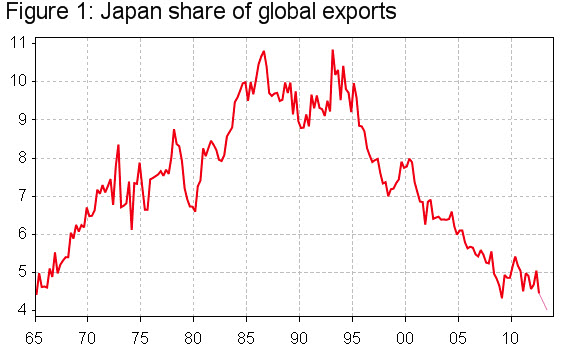

Trade and Growth

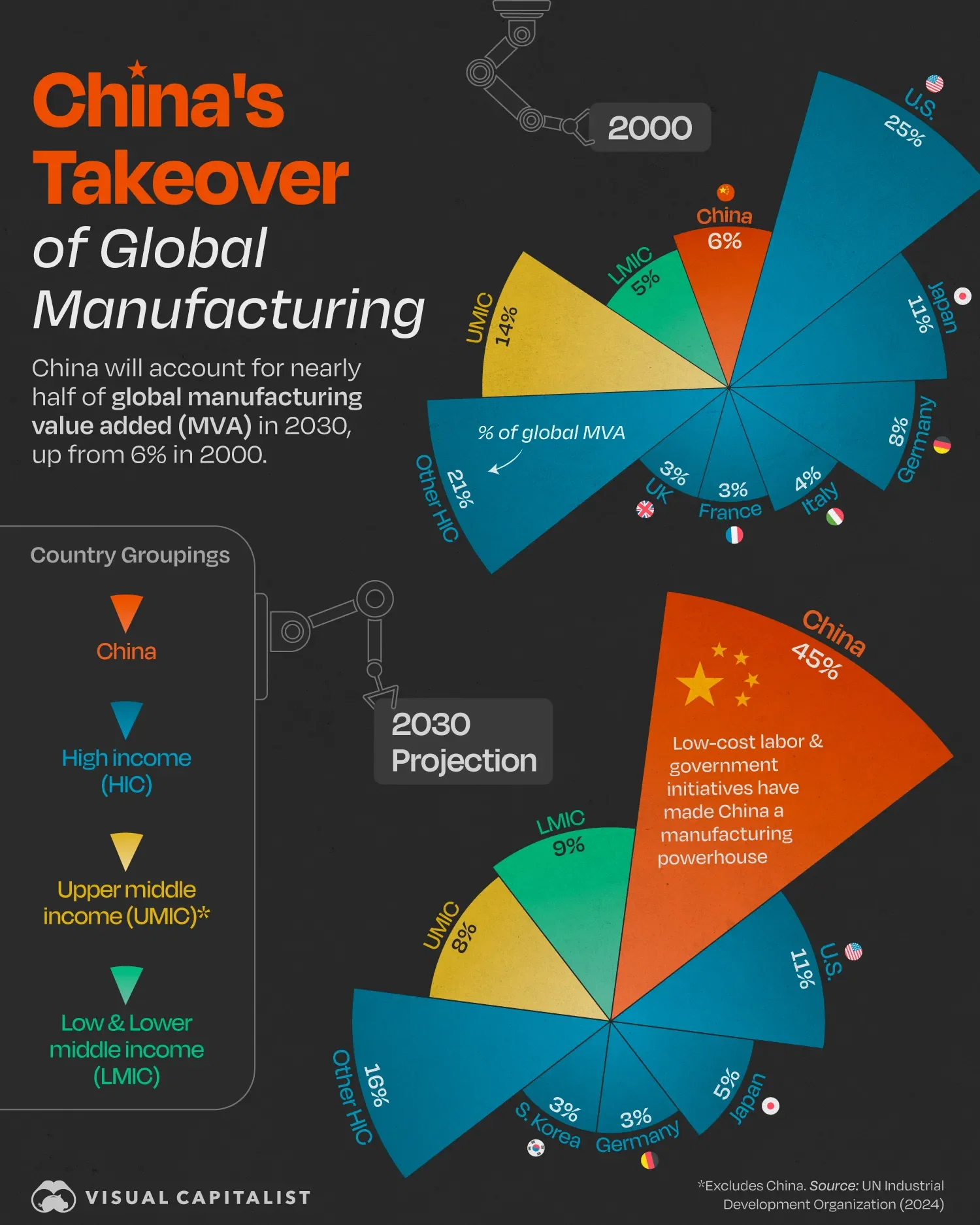

- More recently, China’s economy has grown substantially and many economists point to their emphasis on trade as a main cause

- If we look at Japan’s share of global exports over time, the drop coincides with China’s entry into the world market

Trade and Growth

More recently, China’s economy has grown substantially and many economists point to their emphasis on trade as a main cause

Big question: If we have empirical evidence that trade can help grow an economy, why doesn’t everyone “trade their way out of poverty”?

They’re trying, but its not that easy

Trade and Growth

Trade and Growth

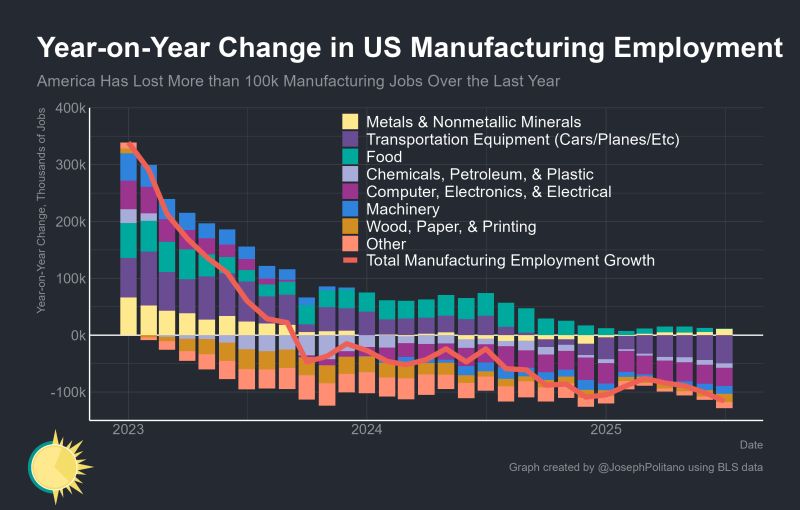

Winners and Losers

Economists like to argue that trade results in the most efficient allocation of production

- Goods are produced where costs are lower

- In general, this results in lower prices for consumers and increased welfare

- However, benefits are not distributed equally across the population

- If the US imports cars from Japan, what happens to US auto workers?

- In theory, those that “lose” from trade could be compensated by those that “win”

- In practice, that does not happen

Backlash From Trade

Recently (over the past few years) there has been a great deal of push back in developed countries against free trade and globalization

- Globalization: The increasing integration of national economies into expanding international markets

This resistance to globalization comes from both political sides

The rise of populism across the globe has been partly attributed to this anti-globalization/anti-trade sentiment

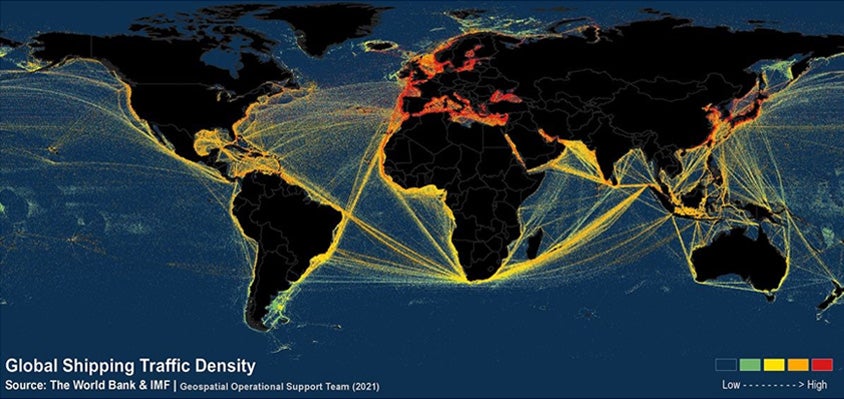

Globalization

As with everything, there are Benefits and Costs

Benefits

- Efficiency gains from trade

- More rapid transfers of technology

- Reduced probability of international wars

- Increased demand for a countries products (exports)

Costs

- Emphasizes inequalities across and within countries

- Accelerates environmental degradation

- International dominance of riches nations

All countries face these benefits AND costs, but the benefits are greater and the costs are higher for developing countries

In theory, the benefits outweigh the costs

Globalization and Trade

Trade liberalization has been key to the encouragement of globalization

Trade liberalization refers to the reduction of global tariffs

- Tariff: A fixed-percentage tax on the value of an imported commodity levied at the point of entry into the importing country

- Trade liberalization has occured through international agreements to lower the costs of trade between countries

- It came into fashion after WWII, when European countries (and the US) signed the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT)

- European countries realized that by integrating their economies they could reduce the likelihood of another large-scale war on the continent

Free Trade and Growth

Free trade: The importation and exportation of goods without any barriers in the form of tariffs, quotas, or other restrictions

Much like free markets, free trade has many desirable properties

- Also like free markets, free trade exists more in theory than in practice

Nevertheless, free trade is what we use as a basis for international trade in economics

Let’s set up a basic model of trade

Model of Trade

Motivation: Developed economies are better at producing most goods. Then wehy do we see countries trading?

Let’s use some simple assumptions:

- Two countries

- Two goods

- One factor of production only require labor to produce any good

- No transport costs

- Our factor of production assumption implies that if we observe trade between two countries, it must be driven by differences in labor productivities across borders

Model of Trade

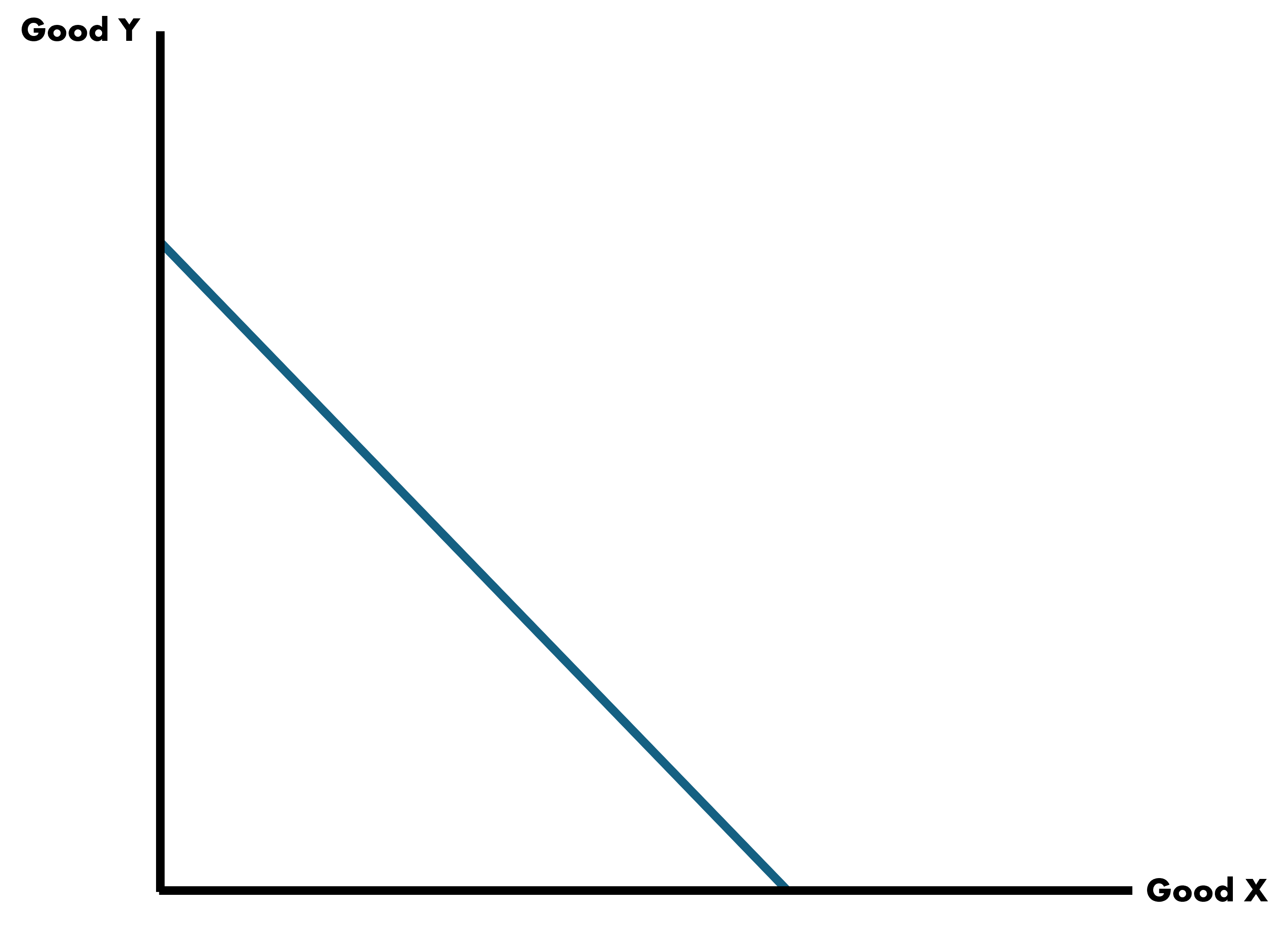

Let’s start with a single country for now and let’s assume there are two goods: Good Y and Good X

Production Possibility Frontiers (PPFs) show all the possible combinations (bundles) of goods that a country can produce

- A country’s budget line

Model of Trade

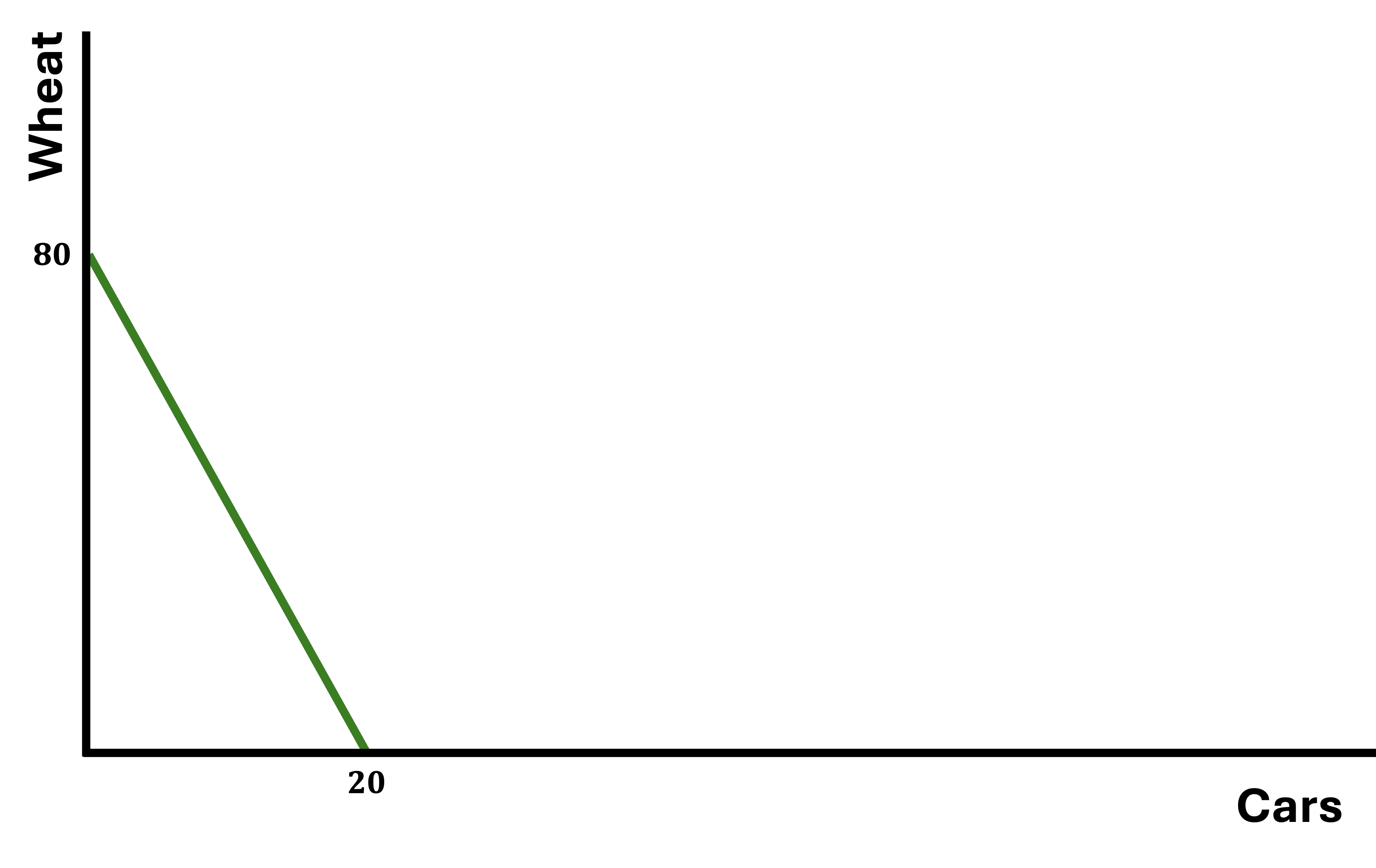

Let’s put numbers to the model

- If the country only produces cars, they can produce 20 cars

- If the country only produces wheat, they can produce 80 units

Model of Trade

The slope of the PPF tells us the opportunity cost of producing them

In order to produce 80 wheat, the country must give up 20 cars

This means that the opportunity cost of producing 1 car is 4 units of wheat

Opportunity Cost

\[ 80W = 20C \rightarrow \dfrac{80}{20}W = C \]

\[ 4W = 1C \]

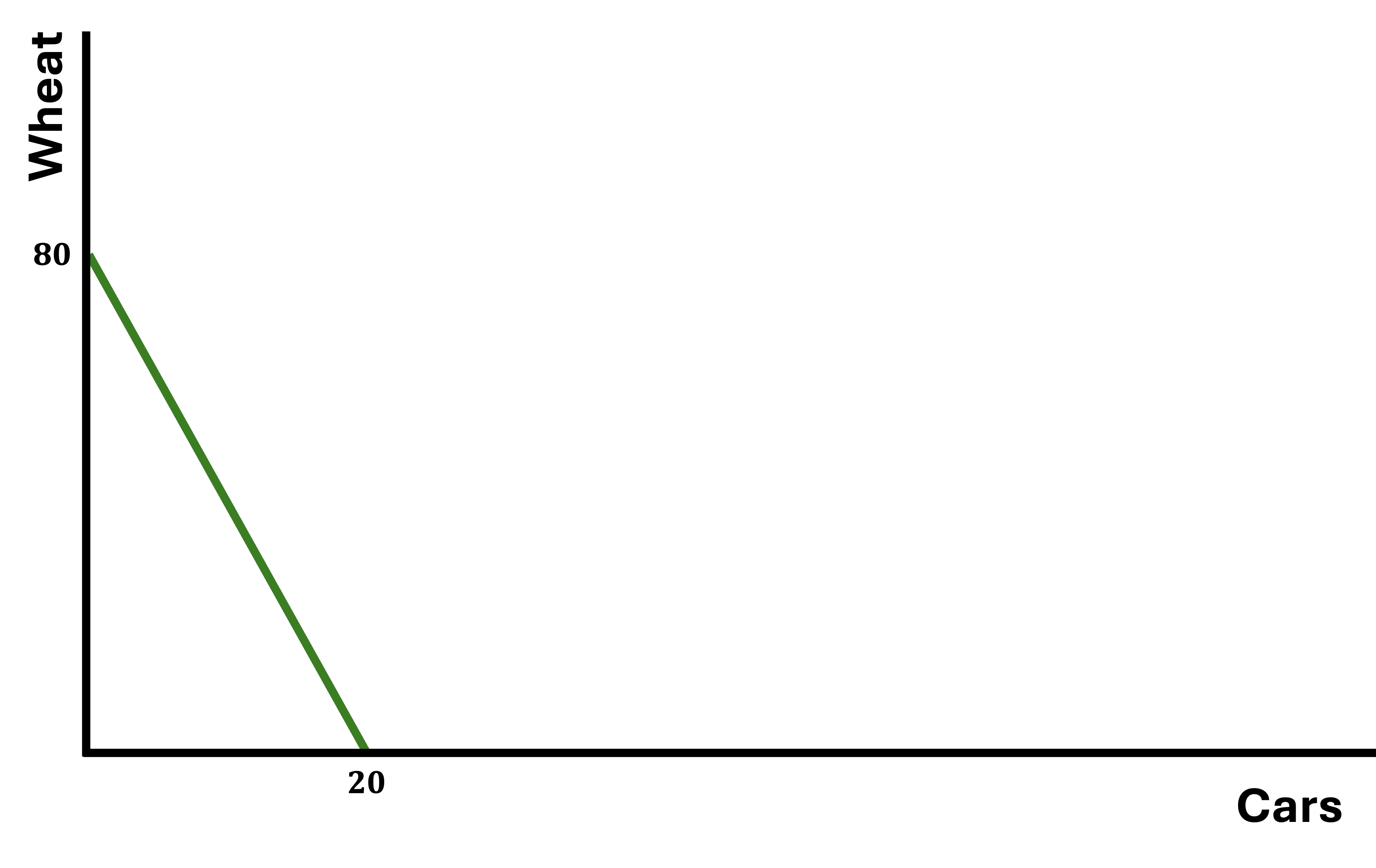

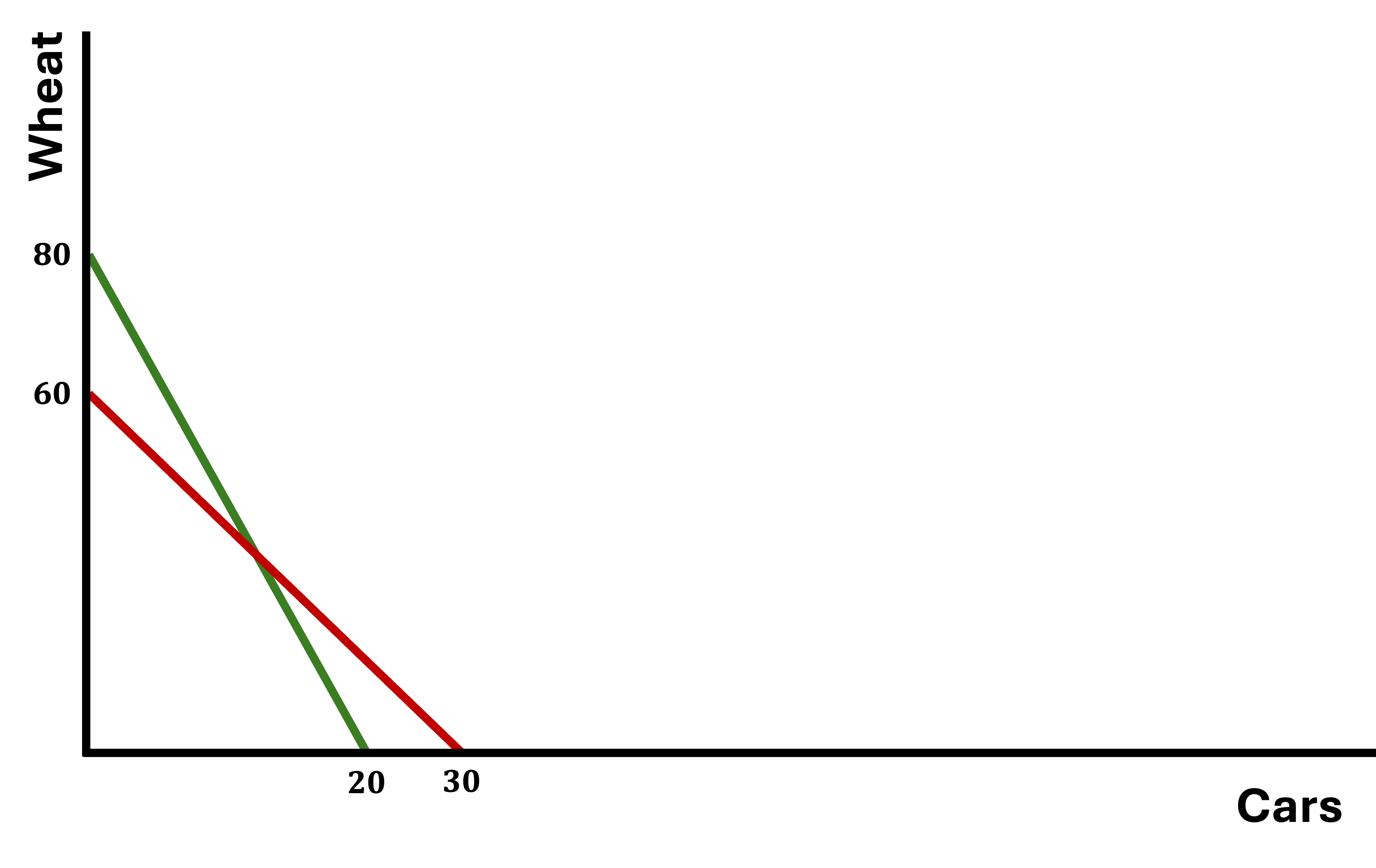

Two Countries, Two Goods

Let’s add a second country

- They each can produce goods at the following rates (if they specialize):

| A | B | |

|---|---|---|

| Wheat | 80 | 60 |

| Cars | 20 | 30 |

Two Countries, Two Goods

Let’s add a second country

- They each can produce goods at the following rates (if they specialize):

| A | B | |

|---|---|---|

| Wheat | 80 | 60 |

| Cars | 20 | 30 |

Opportunity Costs

- Opportunity cost of producing 1 car in country A is 4 units of wheat

- Opportunity cost of producing 1 car in country B is 2 units of wheat

- It is “cheaper” to produce cars in country B

- Lower opportunity cost = comparative advantage

- Trade is based on comparative advantages

Specialization

Our model then predicts that country B will specialize in producing cars and country A will specialize in producing wheat

A and B will then trade with each other so they can both consume cars and wheat

Specialization in the good for which you have a comparatie advantage, then trading with another country should increase welfare for both trading partners

Since both countries specialize in the good that they produce relatively cheaper, the “international market price” will fall somewhere between the price in both countries

- The international price will be higher than the exporting country’s price and lower than the importing country’s price

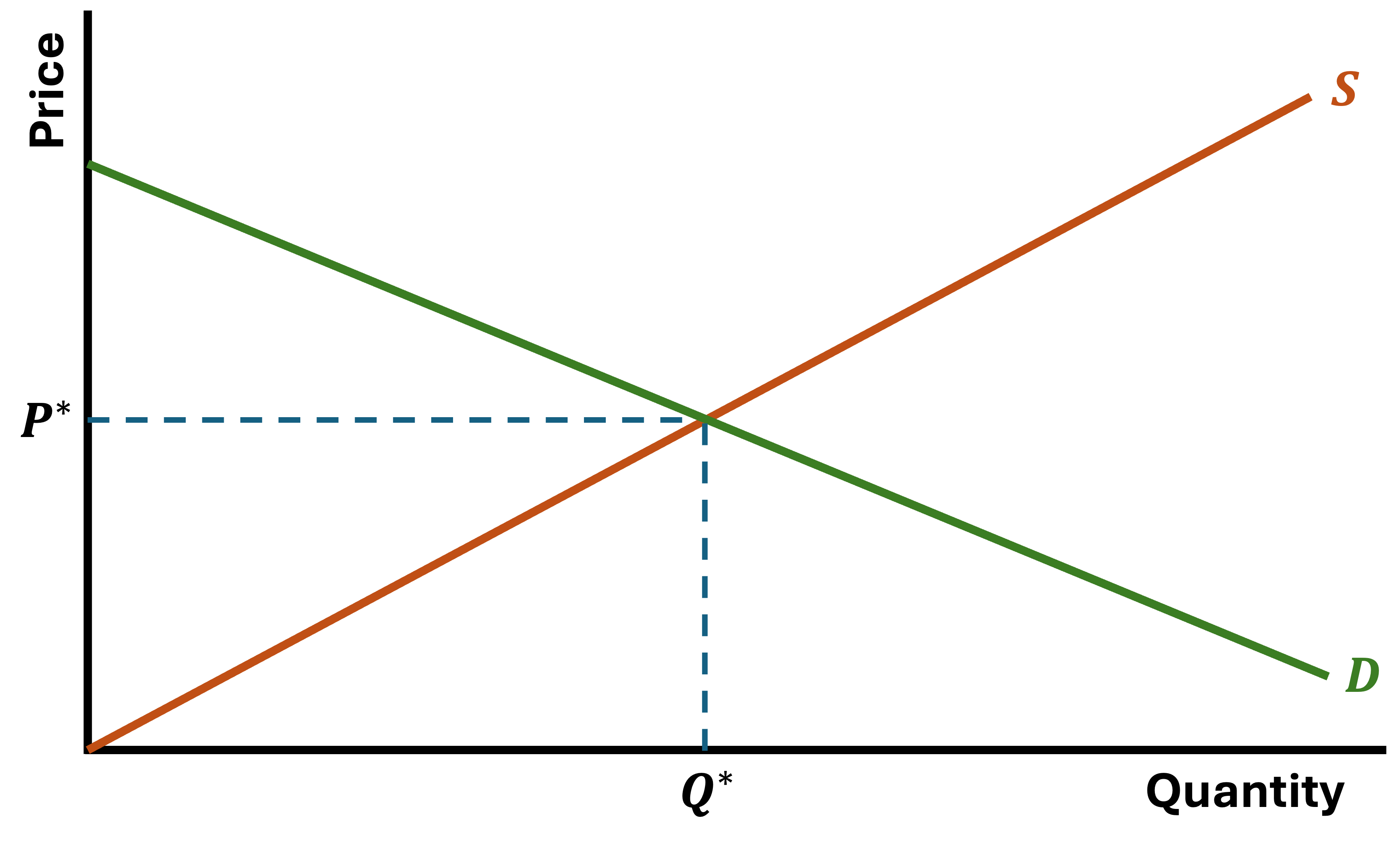

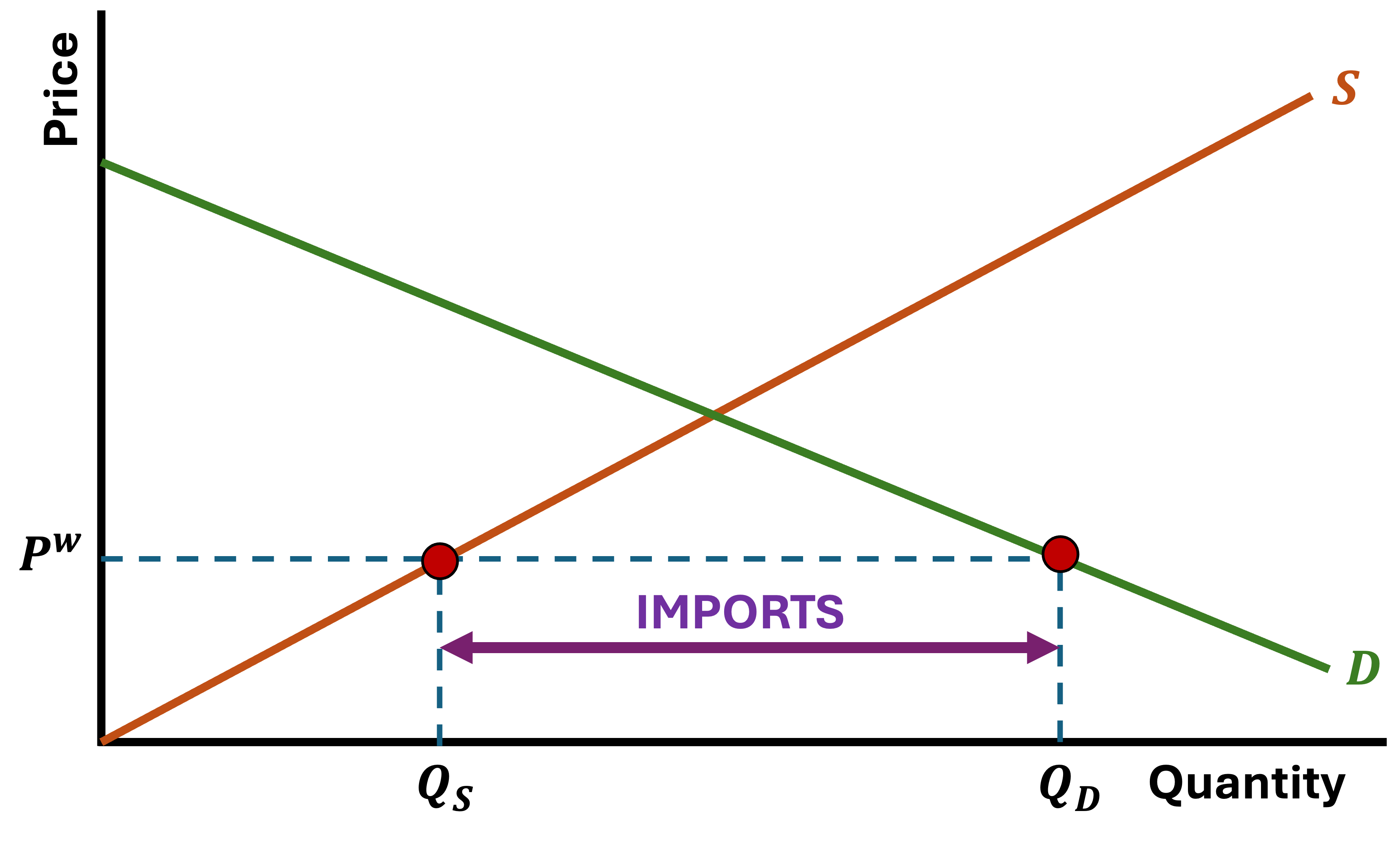

World Trade (Local Perspective)

How does this look like in terms of demand and supply in one country?

Let’s start under autarky (no trade)

World Trade (Local Perspective)

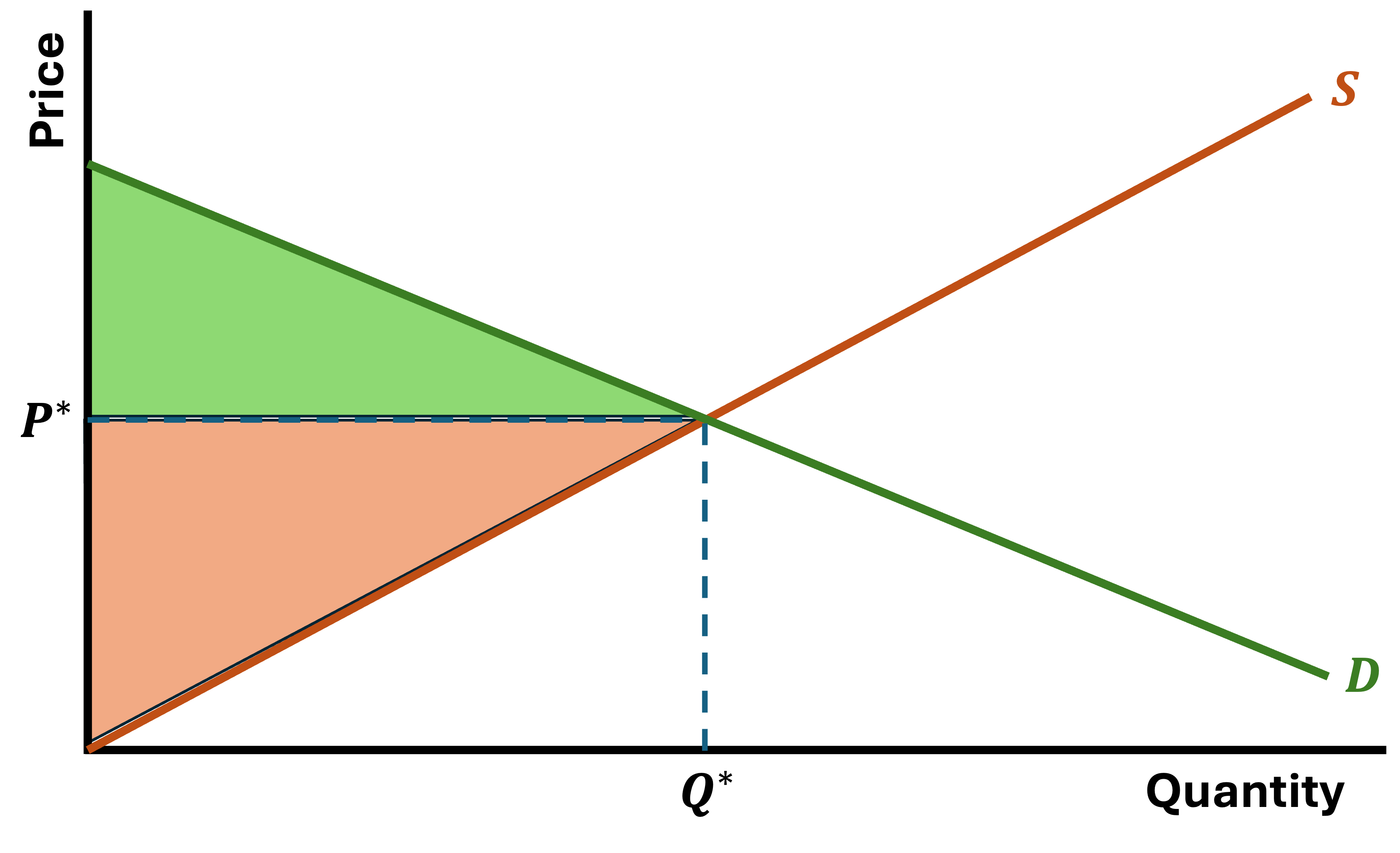

There’s Consumer and Producer Surplus

World Trade (Local Perspective)

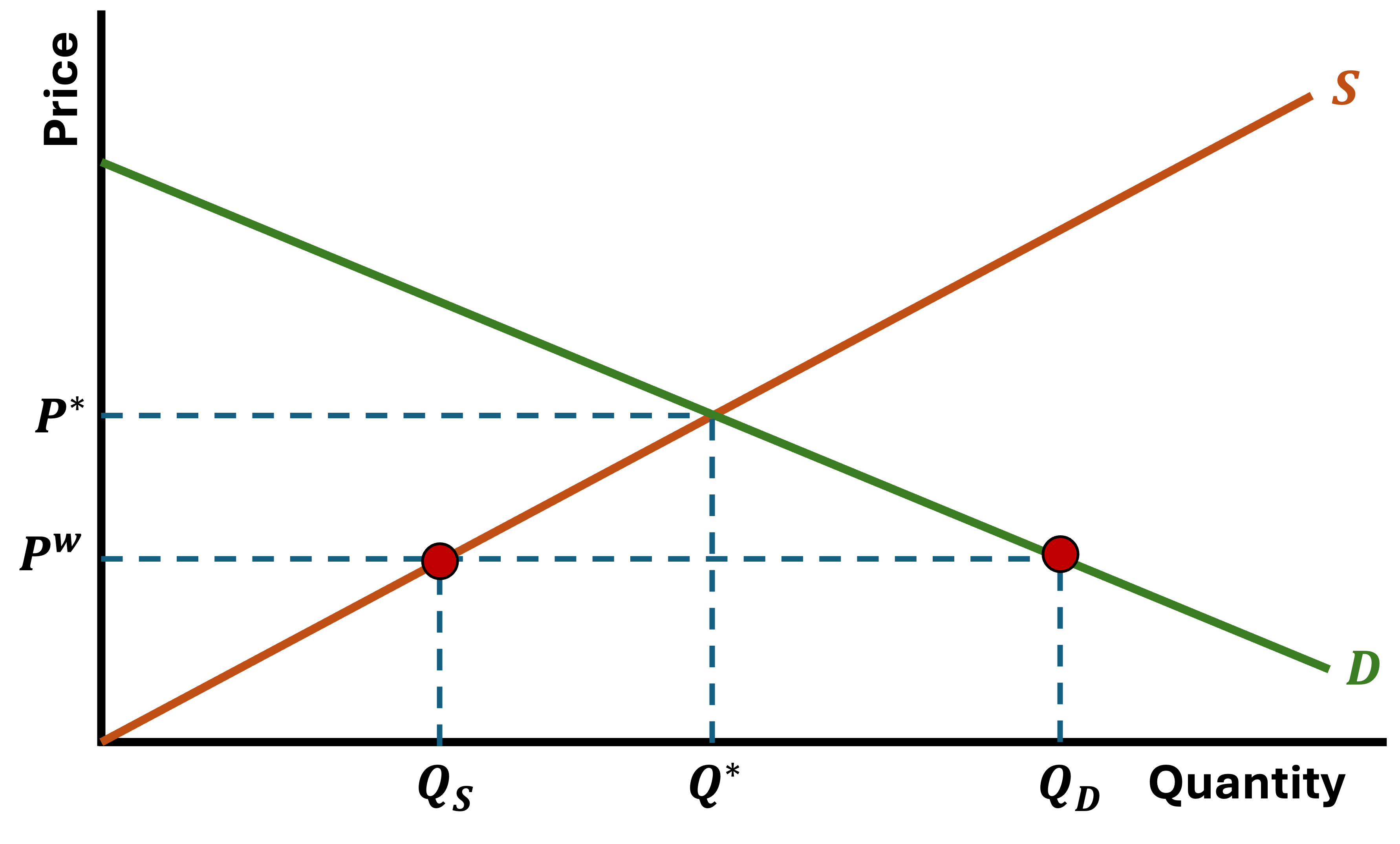

Now we introduce trade, which comes with a World Price

World Trade (Local Perspective)

Because consumers demand more than local producers make, demand must be met somehow

- The country imports the difference

World Trade (Local Perspective)

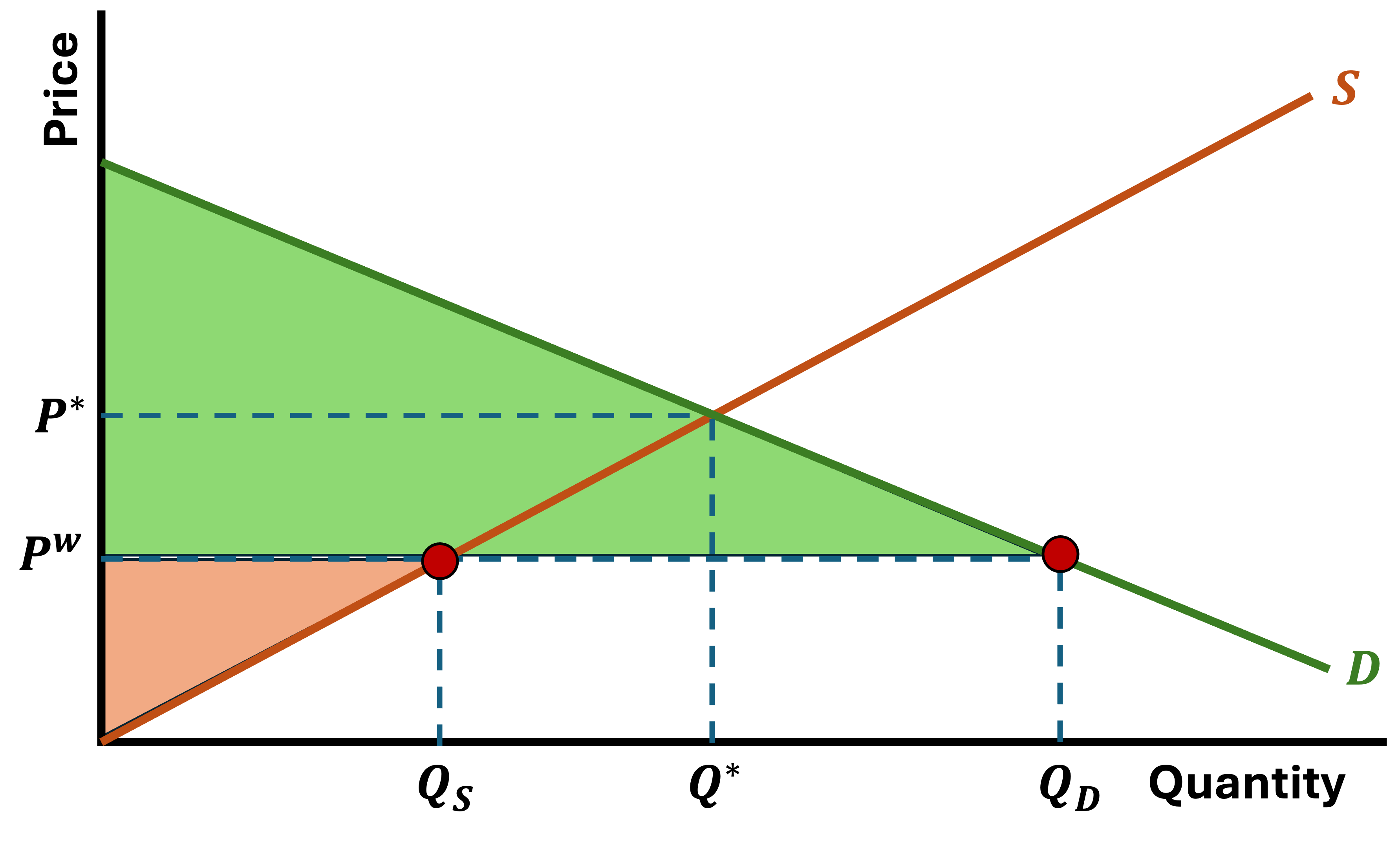

This new price shifts Consumer and Producer Surplus

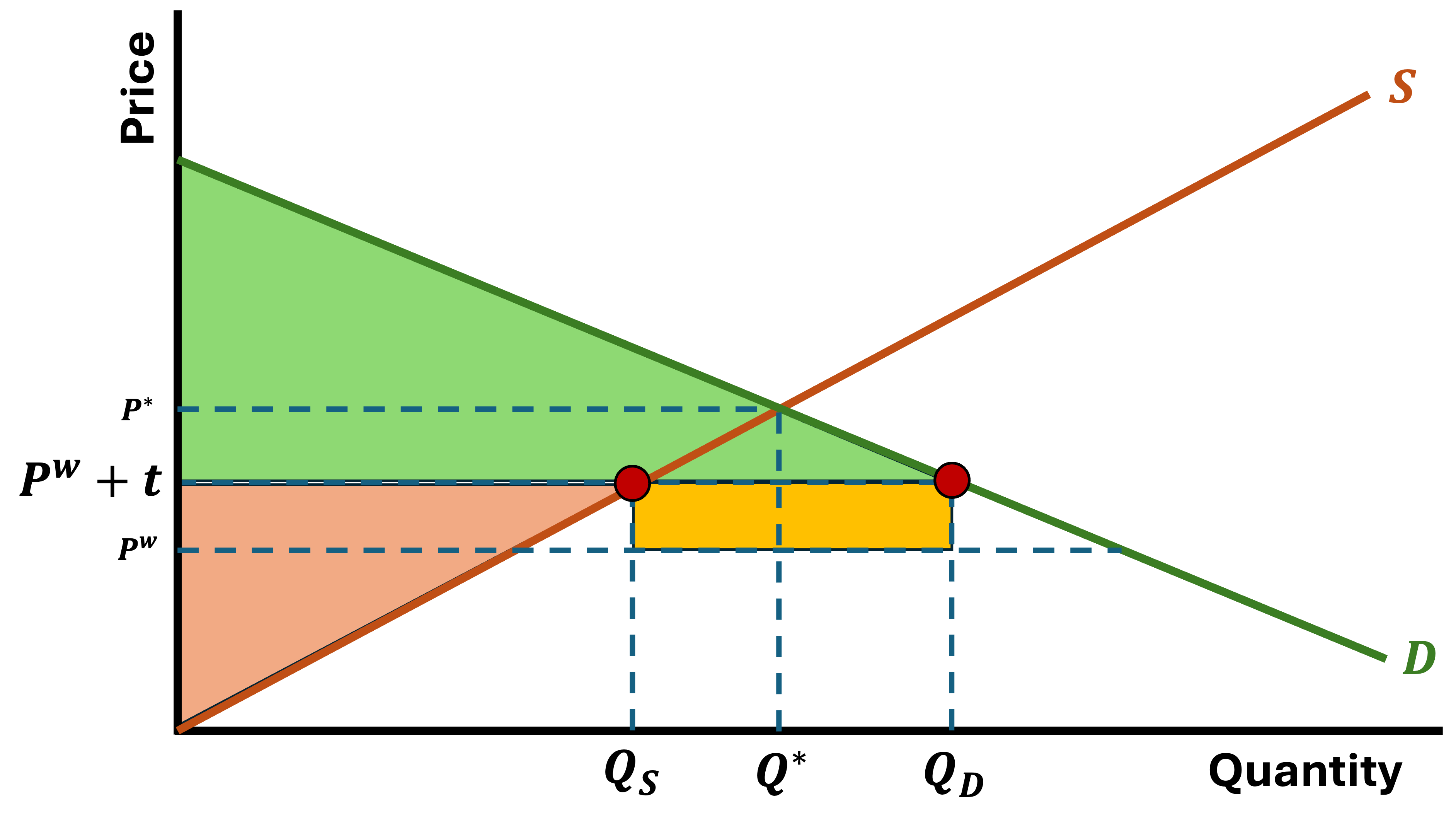

World Trade (Government Intervention)

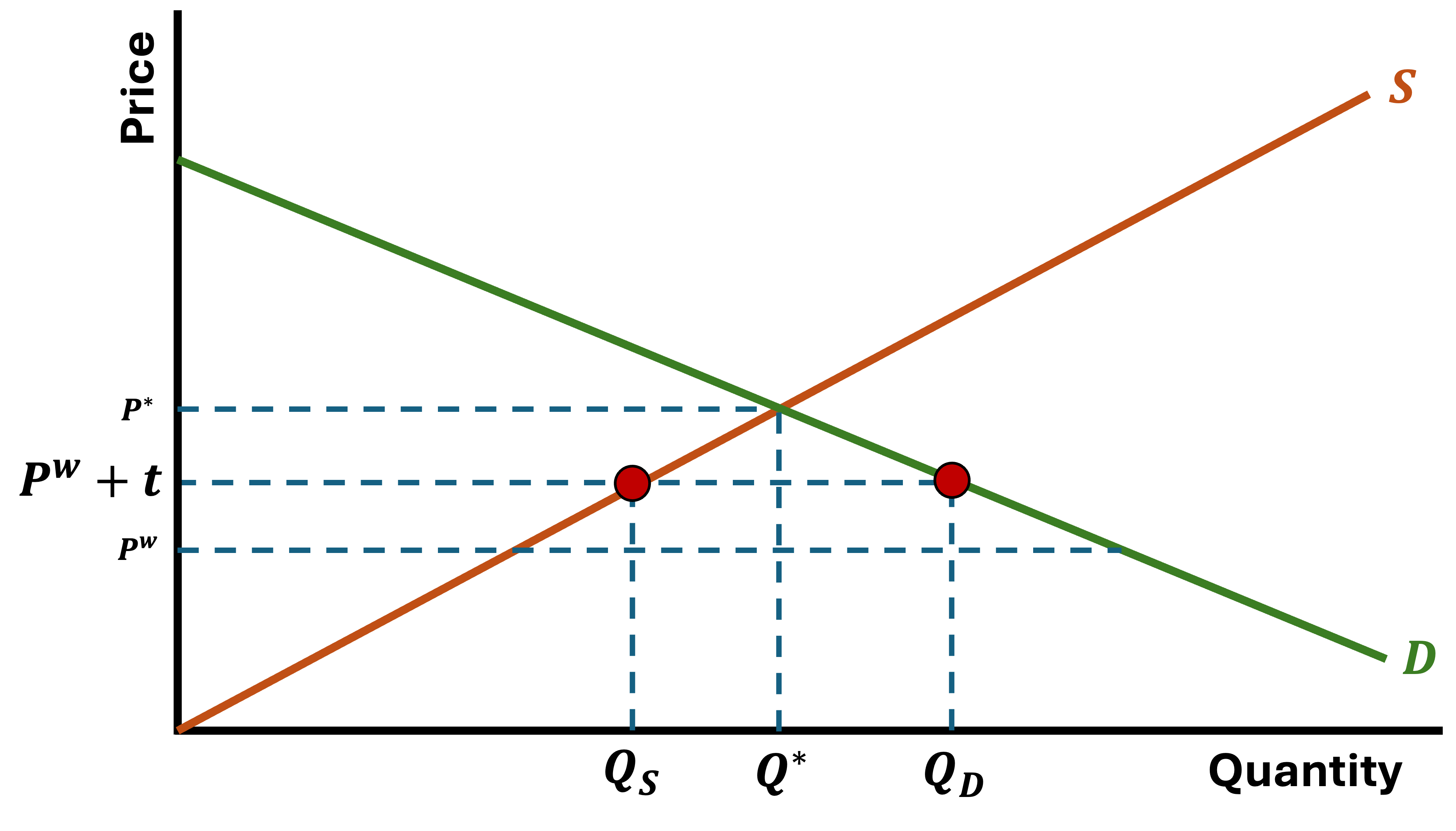

Let’s imagine that the government notices this loss in Producer Surplus and they decide they would like to protect their domestic industry somewhat

So they enact a tariff on the imported good

- This will raise the price of the imported good

- It will generate government revenue

- It will reduce consumer surplus

- It will increase domestic producer surplus

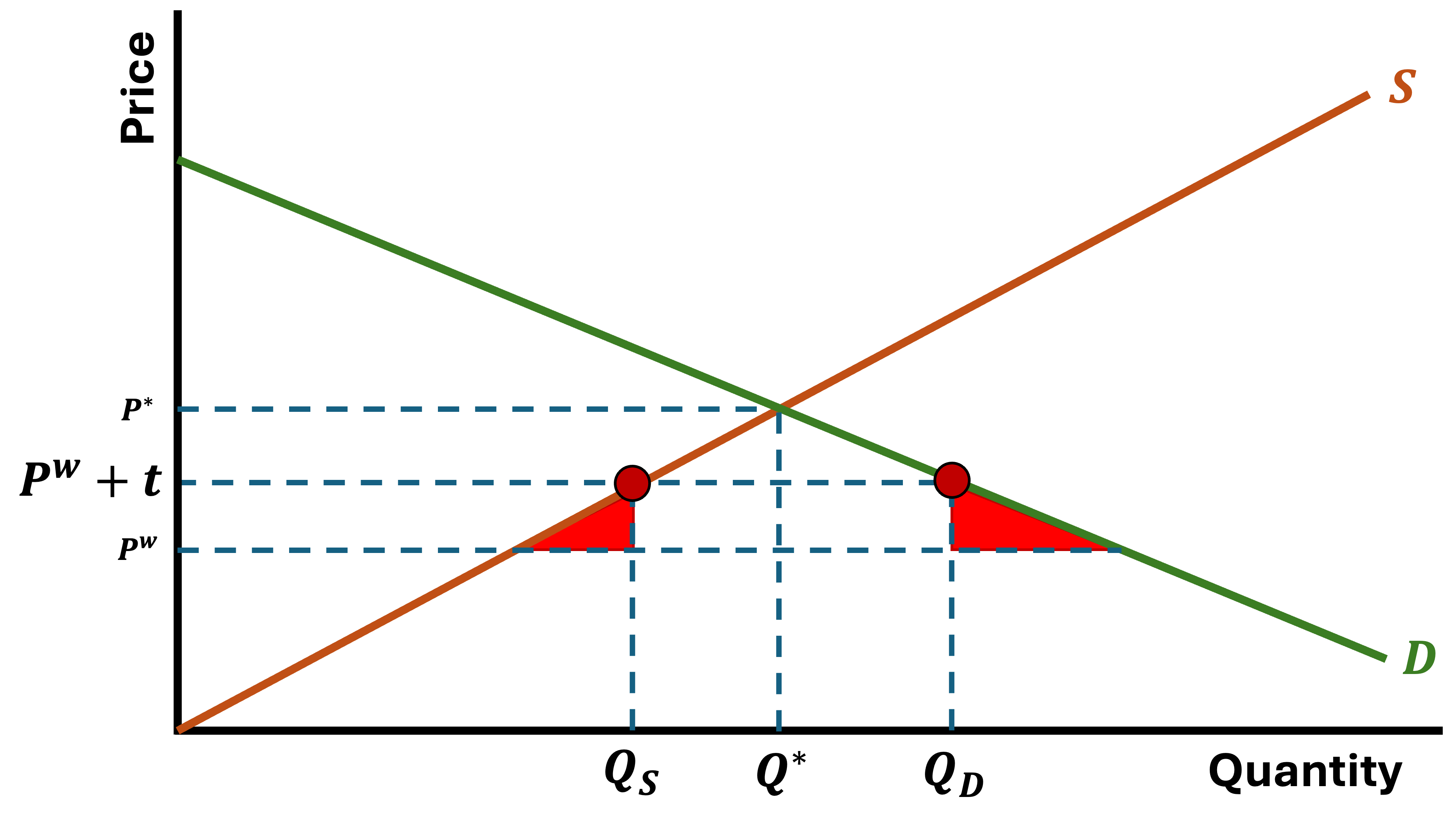

- And it will induce some market inefficiencies (Deadweight Loss)

World Trade (Government Intervention)

Prices go up to \(P^{W} + t\) which produces new quantity demanded and supplied locally

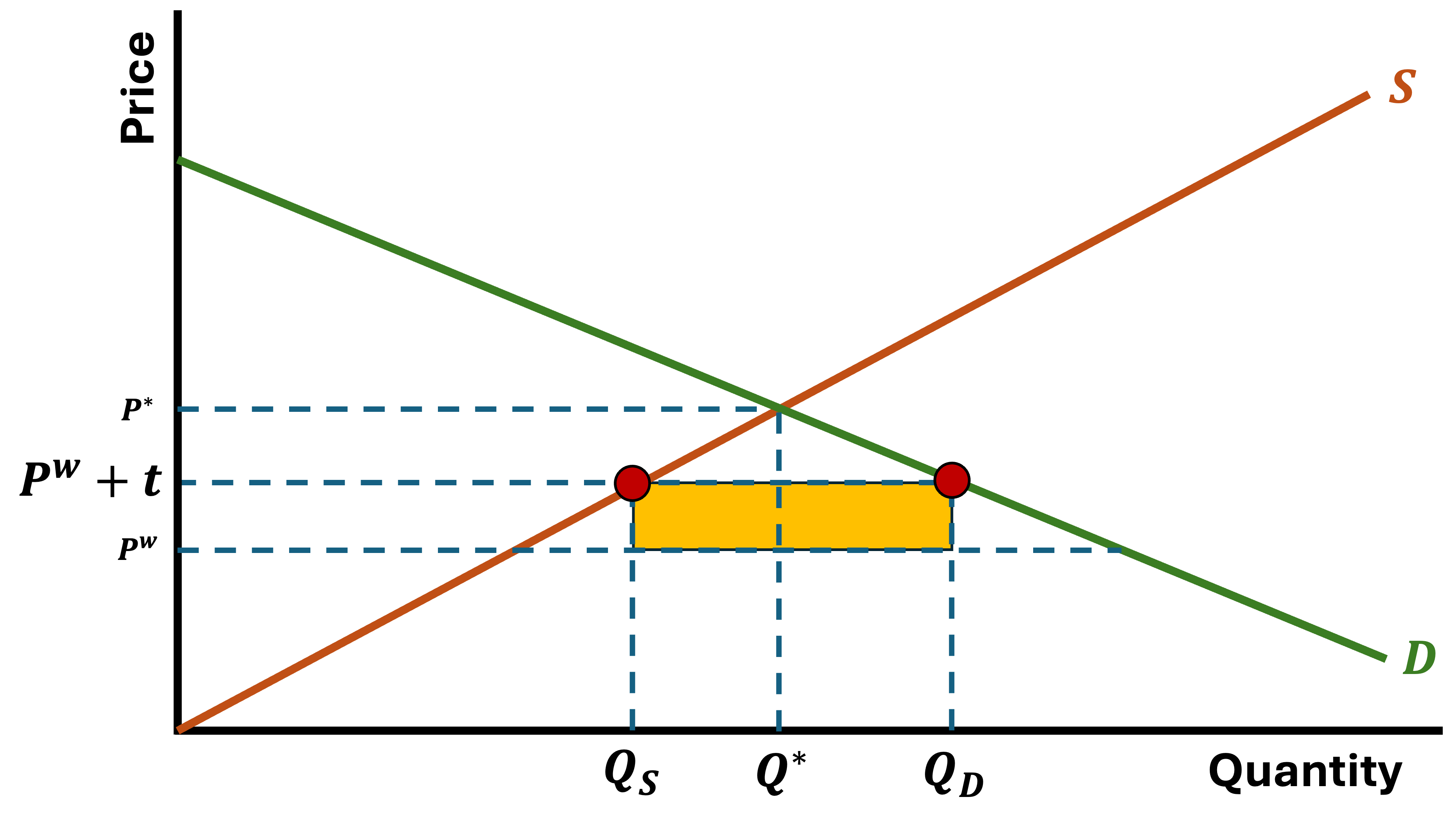

World Trade (Government Intervention)

The Government collects tariff revenues \(= \text{Imports} \times \text{tariff}\)

World Trade (Government Intervention)

Consumer Surplus shrinks slightly and Producer Surplus grows

World Trade (Government Intervention)

The tariff (tax) creates inefficiencies (Deadweight Loss)

Developing Nations and Trade

There are two main strategies that developing countries have taken when faced with increased globalization

Import Substitution Industrialization

- Development strategy to promote domestic production of imported goods through protectionism and state intervention

- High tariffs

- Subsidies for Domestic Industry

- Goal is to break dependency on foreign commodities

- Create domestic industrial capacity

- Inefficient

- Small domestic markets limited scale economies

Export Promotion

- A strategy centered on integrating domestic firms into global markets, incentivizing production for export, and fostering competitiveness

- Low or moderate tariffs toward gradual liberalization

- Incentives for foreign direct investment

- Learning-by-Exporting

- Requires strong state capacity and credible institutions

- Can create enclave sectors dominated by MNCs

EC390, Lecture 10 | Trade & Foreign Aid